Toronto, Ontario

Canada

Sisters ELIZABETH YEOMAN and SHEILA YEOMAN are collaborating on a portrait memoir of their adventurous great-aunt. Here they share some background and thoughts on their work-in-progress.

Please begin by telling me a little about yourselves.

E: We are from Dorchester, New Brunswick, where we grew up in a large stone house built in 1831 and permeated with history. I am now a professor of Education and Women’s Studies at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Among other things, I teach courses about narrative and life history, so this project relates somewhat to my professional work.

S: I’m the assistant curator of the history collection at the Nova Scotia Museum in Halifax. My professional specialty is costume and my personal specialty is riding habits and the history of sidesaddle riding for women.

Who and what is your memoir about, and do you have a working title?

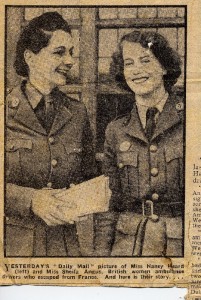

E: Two titles we thought of are: We Had to Share Lipstick (taken from a headline in a Daily Telegraph article about how our great-aunt and another female ambulance driver escaped from France with wounded men in their ambulances), or Champagne and Strawberries with Airmen from another newspaper article. So, to backtrack, the project is based on the wartime diary and photo albums of our great-aunt, Sheila Angus, who drove an ambulance in WWII in France and Egypt, as well as correspondence with her sisters, newspaper clippings and other miscellaneous documents.

What inspired you to write about Great-Aunt Sheila?

S: Our interest in this project started with a story our mother liked to tell about a particular event during the fall of France and our aunt’s involvement. It was a very dramatic story. Ironically, although the story itself was true, we found out once we started researching this that our aunt was not actually there. Nevertheless, she had many other adventures—and we probably wouldn’t even have started this project without our mother’s story.

As well as having all the material culture, I was drawn to her because she never married, was very independent, and travelled a lot—and I was in a feminist phase. I wanted to be like her! Also because she liked animals and so do I.

E: I had some feminist/women’s history interests too, and also interest in the two world wars. And the photos and diary were just fascinating.

How unusual was it for a woman to be an ambulance driver in WWII, and how did your great-aunt get involved?

S: Not unusual at all in WWII, or even WWI. I was wondering how she got involved actually. I think she just wanted to travel and do something exciting, and “do her bit” for the war effort. And she probably liked driving. I think she started out in London in the early days, doing first aid or fire-watching or something. There’s a photo taken in London with a group of people in 1939 and they look like first-aiders, and the back is covered with autographs—I have yet to figure out details like this.

E: Though it’s true it wasn’t unusual, it should be noted that many of them were from relatively privileged backgrounds, since not all women could drive in those days and the ones who could, must have had access to a car.

You’ve said that Sheila’s diary entries during the war were not what you’d expected. In what way?

S: The diary wasn’t battle oriented and also it wasn’t about her own work as a driver, but more about her social life, which makes sense to me now, but when I first read it I was surprised.

Through her diary have you made any discoveries about the woman, or her times, that surprised you?

E: Yes, a lot of interesting things about a rather scandalous love life (at one point, she wrote “What would Mummy think of me if she knew?” and elsewhere, about married men she was involved with, “One wonders what they’re like at home with their wives . . .”). And she could be very entertaining and funny, which we didn’t experience in person (for instance, describing a beau of a fellow driver as “A real old sugar daddy. Looked as though he’d melt in the sun”). Also some comments she made are quite racist and classist by today’s standards. It’s difficult to know how to handle those aspects.

S: I had wondered if she was a lesbian, but the very heterosexual love life seemed to dispel that idea. Another thing that struck me about her diaries was that she seemed bored with the work she did. I guess that’s the nature of war though.

E: Somebody famous (I forget who) said that war is long periods of boredom interspersed with brief periods of terror.

You were raised in a family that valued the preservation of history, weren’t you. How has that influenced you?

E: Yes, imbued with history from a young age! Our mother won the Order of Canada for her work in heritage preservation in New Brunswick and involved us in many of her projects.

S: Mum was Chair of the Museums Association New Brunswick and she initiated Dorchester Heritage Properties. It started in 1967 with a Centennial project, Keillor House Museum, which was down the street from our house—early days of my life. I remember riding on an antique riding toy in the museum. Horrors! (museum curator speaking). Mum “ran” Keillor House Museum from 1967 to 1997. The mandate of Dorchester Heritage Properties was to preserve historic buildings in Dorchester but also to create things for the village in modern times: a café in one of the buildings, workshops on making reproduction costumes, job creation . . . I guess I learned at my mother’s knee because I ended up going to art college (like Mum), switching to costume studies (like Mum), and later working in a museum (like Mum), even though I didn’t plan to.

E: Also, the sense of living in a heritage house—“Rocklyn,” built in 1831 by Edward Barron Chandler, one of the Fathers of Confederation—where others had gone before us. We had pictures of earlier generations of children and a cookbook that had belonged to the original “lady of the house” in the mid-1800s, and knew quite a lot about them. Actually, now I think about it, that’s another project Sheila and I collaborated on, a long time ago. It was an illustrated children’s book, kind of a ghost story but not a scary one, in which we imagined the generations of children living side by side and doing parallel things, though in their different historic contexts. It didn’t get published though. But maybe we gave up too soon. As I said, it was a long time ago and we didn’t have much experience with publishing.

In addition to a mutual passion for history, what skills do you bring to your individual roles in this project?

E: In addition to my professional background, I’ve done a lot of scholarly writing over the years and try to do some personal and creative writing as well when I have time. I’ve had pieces on CBC Radio (Ideas, Outfront and Commentary), on the Women’s Television Network, and in The Globe and Mail and several literary magazines. The Outfront piece, “Searching For Rachel Martin,” was about my attempt to confirm a piece of family oral history that our 4-x-great-aunt Rachel had been the first woman to navigate a ship across the Atlantic. I was never able to prove or disprove that, but I was surprised by how much archival material I was able to find relating to a relatively ordinary woman who died in her nineties in 1867—and I ended up making a piece about my search and what I did find out about her life. And I learned some archival research skills as well (not the kind of research I do professionally), and LOVED that part. I could spend my life reading old documents in archives.

S: I’m the keeper. Our mother brought Aunt Sheila’s papers and photo albums home from England after she died and when her estate was being auctioned. A cousin had cleaned out the house and my mother took all the personal papers and photos. They included her wartime diaries and photo albums as well as newspaper clippings, a published memoir by another driver (the senior officer) and another diary written by a third driver, who had been captured by the Nazis and then let go, describing what happened to her.

I was living at home with Mum after that so I went through all the diaries initially, then decided to transcribe them to share with family members. I was also in the early stages of my museum career so I made initial attempts at organizing the stuff. Recently I went back to it and started organizing better, storing things archivally, collating, scanning . . . A financial and time investment. My museological and archival skills had grown through ongoing museum training and experience in the meantime. Plus I have a psychological makeup that makes me obsessive about doing things like this.

E: Me too!

Living in separate cities, Halifax and St. John’s, what process are you using to work together? Do you find the distance an issue?

E: Not really. We use e-mail and the phone, and Facebook to share photos, and we usually spend time together at least a couple of times a year.

Have you gone beyond Great-Aunt Sheila’s diaries, photos and correspondence to other sources?

S: There are also generations of photo albums and papers from her family, so we have an awareness of the bigger picture as we work on this project. I have Aunt Sheila’s whole life in photographs, really. Also, Penny Otto’s obituary (Penny was a fellow driver and a lifelong friend of our great-aunt) was sent to us by a British friend of Elizabeth’s. And there are useful links on the Internet, such as the Mechanised Transport Corps website.

What part do your personal memories or those of others play in the book?

S: She visited us here once or twice when we were kids, and as young adults each of us spent time visiting/staying with her in England, Elizabeth more so than me. I always felt inadequate around Aunt Sheila, and too quiet.

When she was still alive we didn’t have the documentation or know much about her life so it didn’t occur to us to ask. One time I did ask her some questions about her life because I had feminist interests in her story, as I mentioned. I was trying to find out if she had made decisions from a feminist perspective, but she didn’t seem interested in talking about the things I wanted to talk about. Maybe I was the wrong person for her to talk to. Maybe she was a natural feminist in terms of the choices she made, but I don’t think she considered it in terms of women’s issues. She just did what she wanted to do. I think also she lived in the present and was less interested in the past than we are—though as we discovered later she did do a fair bit of documenting!

E: Of course, she came from a very privileged background and so she had choices. I think even today women who have been privileged or lucky often don’t see the need for feminism.

We interviewed her sister, Aunt Basie, not long before she died and Sheila asked her if she thought there was anything Aunt S. regretted about her life. I think Sheila was trying to get some information about her love life, but Aunt B. answered the question with, “I think she regretted not having taken up the violin professionally as she was very good.” This was very surprising, at least to me, as I had not known that she was so musical, though she did have a wonderful antique harpsichord that I used to play when visiting her.

Our mother and grandmother also had stories about the two aunts in which their personalities were contrasted, with Aunt S. cast as very strong, accomplished, demanding and determined, whereas Aunt B. was seen as laid back, slightly lazy, easygoing. For example, in one story, they went to a Swiss finishing school and Aunt Sheila worked very hard and learned fluent French whereas Aunt Basie only learned how to order a few choice menu items and nothing else. And now I think of it, some of these stories and the personality they reveal (or create!) may be of interest as background for the memoir. Another memory we all share is how cold and uncomfortable (though beautiful) her house was. And a cousin, also her great-niece, remembered in some awe that she used to swim in the English Channel in her sixties—which I thought was funny because in fact I think she was still swimming in the channel in her eighties.

And last but not least, a few years ago my husband and I visited the house she used to own and the current owner said (also somewhat awed) that she had died because she broke her hip skiing at age 89. I don’t think this (the skiing part) was correct but it is a typical Aunt Sheila story. All the stories were of how indomitable she was and that is how she has entered the oral history of her family and of the village where she lived.

S: I think she actually broke her pelvis while on a holiday in Corfu!

What questions do you wish you could ask her?

E:

- Whom did you admire?

- Why didn’t you take up the violin professionally?

- Tell me about your mother and her family [just as a way of getting back another generation in the history of the family—the question we always think of asking too late!]

- Tell me about your fellow ambulance drivers.

- What was/were the best period(s) in your life and why?

S: I’d like to ask her about her love life (but still wouldn’t dare). And as a long-term animal rights activist, I’d like to know about her anti-blood-sport leanings (despite her father being a Master of Foxhounds!).

Has working on this project influenced your feelings about recording your own life experiences?

E: I kept diaries for many years and now I have a blog Dinner in Strange Places, not updated nearly as often as I would like though!) and am working on some radio pieces relating to my own experiences and family history.

S: I’ve kept all kinds of stuff from my whole life. People are always amazed at the stuff I have! Somehow it makes me feel my life was more concrete if I have documentation. I still keep copies of letters I’ve written, but I’ve gone more into the visual realm with photos more than words.

E: Though, Facebook interestingly combines words and images . . . Some members of our extended family have been using it to do family history, share photos, documents and information, and our more immediate family seems to be doing some collective “shrink-age”—our term for mutual psychoanalysis—sometimes in response to particular family photos!

Do you see any larger theme or themes emerging from your research?

S: It’s a slice of the World War II story. Also, through discovering the characters and choices of that generation of women in our family, I can see the effects on our generation.

E: Themes about stories and the way they’re told and remembered—the original story that wasn’t true and yet was important because it got us interested. And a story from her diary about riding a camel in Egypt and it running away with her towards the German encampment. It’s a funny story, but that was probably terrifying in reality. In my experience, people who have lived through war either tell funny war stories or don’t talk about it at all, or very rarely. So a theme that interests me is how narrative works to give coherence to inchoate experience, and how it can enable some people to talk about living through trauma in a way that isn’t too painful. Only some, though, and only somewhat.

What are the biggest challenges you’re facing in deciding how to write your great-aunt’s life story?

S: Some family members weren’t sure it was a good idea to publish the diary because of privacy issues, etc. But we feel they are of historic interest, and she doesn’t have any descendants and is no longer living herself.

E: And probably if someone keeps a diary they have some idea that somebody else will read it someday, and that they are keeping a record. I think. But as I mentioned earlier, it’s difficult to know how to handle certain aspects: we don’t want to do revisionist history but we don’t want to make her look bad either!

S: Also gaps in the documentation are a challenge.

What published memoirs have inspired you—ones that you might consider as a model for your book?

S: I really liked Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family, though maybe that’s too much to aspire to. I imagine our final product as having a lot more images than he used though.

I also was inspired by some women’s wartime memoirs such as Vera Brittain’s books (though she didn’t use any pictures, I don’t think) and collected anecdotes like one called Unsung Heroines: The Women Who Won the War and another called Wartime Heroines. I really liked Relative Stranger too—perfect title for one thing! I’ve also read and enjoyed many biographies, usually about somewhat eccentric and/or artsy women of the past, e.g., by Victoria Glendinning.

E: I also loved Running in the Family. I read lots of memoirs and family histories and have loved many of them, too numerous to mention! A few examples are Hilary Mantel’s Giving Up the Ghost, Mary Loudon’s Relative Stranger. Edward Ball’s Slaves in the Family. A friend of mine didn’t like that one because he kept having to refer back to the images, charts and maps all the time, but I really liked that. Almost like hypertext. Actually I think the Internet has extraordinary possibilities and I have seen some wonderful examples like Don Austin’s “Ned After Snowslides,” a memoir of lost love, which is absolutely brilliant. Every time I look at it I feel happy just knowing he lives in the same city I do (at least I think he still lives here). I also admire Anne Marie Fleming’s documentary film and graphic novel about her great-grandfather, Long Tack Sam, a Chinese acrobat. There is an interview with her on the Smith Magazine website: OK, we could both go on and on with this question, but enough!

I know you haven’t decided on the final form of your project, but do you believe the story is of interest to a wider audience than your family?

E: I definitely think it is of wider interest.

S: I’ve always pictured a book with lots of pictures. I haven’t pictured much interpretation, just an edited version of the diary and related papers with images.

E: That’s what I imagine too. With perhaps an introductory essay. I have thought of making a film as well. Or a graphic novel with photos and some drawing to fill in the gaps we were worrying about earlier (see Anne Marie Fleming for an example). I’ll never get that much drawing out of Sheila though, although she is actually an extremely talented artist.

S: Oh no, don’t say that!

So when is your estimated date of completion for We Had to Share Lipstick?

S: We’re starting to think about that now . . .

I understand you’ve collaborated on other projects as well.

E: We also collaborated (with another sister as well) on a short piece about our father for a book about Dorchester, N.B. veterans of WWI and II, and on a self-published book (just for family) about our ancestors through the female line called Sarah’s Line. Sarah Godwin was the furthest-back ancestor we could find through the female line, hence the title. She emigrated from England to Australia in 1791 after her husband was transported there in the second convict fleet. It does seem almost as though she founded a dynasty, because she went to Australia absolutely destitute soon after the death of her only child but ended up having other children in Australia and from them came a multitude of descendants all over the world and of many different races and ethnicities today (black, white, Asian, Native Canadian and Polynesian).

We published the book using the Mac iPhoto software and I found it incredibly freeing to just do it exactly how I wanted, after so many years of doing scholarly work, which has to conform to all sorts of standards. I don’t mean I wasn’t meticulous in writing Sarah’s Line, but I wrote in the style I wanted and did not worry about referencing everything and things like that (though now I would like to do another version that does give all the sources!). It was also very exciting working with Sheila as any time I wanted a certain image I would e-mail her and it was amazing how she would always come up with exactly what I needed! It was fun getting in touch with some of Sarah’s other descendants around the world through the Internet too.

S: Also, around 1990 I did an early version of this project about Aunt Sheila as a gift for one of my sisters. I typed the diary and printed it out on dot matrix, then photocopied the photos and pasted them in manually in the appropriate places. It took a lot of time, but I liked writing on the computer—which was new to me at the time—compared to writing things longhand.

What do you see as the rewards for the two of you in working on a project such as We Had to Share Lipstick?

S: We have made other connections through the Internet. And filling in the gaps is rewarding. For instance there are loose photos from when she worked with Palestinian refugees, but she didn’t keep a diary during that time.

E: I just find it endlessly fascinating. Someone described family history and genealogy as “a worm’s eye view of history” and maybe it is but I find the stories of ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances absolutely compelling. And sometimes the stories of ordinary people in so-called ordinary circumstances are pretty amazing too. As Anne Marie Fleming said about her projects on her great-grandfather: “It’s like a revisit of the twentieth century through the prismatic nature of this one particular man. It was like an ever-expanding puzzle as to issues of race and identity and global travel. That is the story of my family. Through my own journey, I learned how much it is the story of so many families.”

I think that’s true for our story too. It’s the history of WWII in Europe and Africa, and Palestine after the war—the “ever expanding puzzle” of all those contexts is still with us today.

Copyright 2009 Allyson Latta.